Judge Casey’s Daughter

Honorable Judge Bray, officers of the Contra Costa Historical Society, old timers of Port Costa, and ladies and gentlemen:

When Mr. Stein called me to ask if I would give a fifteen-minute talk on my father, the late Judge Casey of Port Costa, I wondered what I could say that would require that much time. However, when I began to reminisce, it wasn’t long before I realized that it would be hard to confine myself to extemporaneous spreading. No, I thought it best to put down on paper the salient points which might prove of interest in order that the gathering would not be delayed beyond the point of patience. I have not attempted any history of the town as the historiographers, I know, would take care of that, but, rather, the humorous and homely little incidents that made the old home town unique among small places. To many of you here tonight the name Port Costa will mean nothing much more than another small community, which has seen its heyday but to myself and the other old timers here today (and we are the old-timers now) it will, I’m sure, bring back very pleasant and poignant memories of our carefree childhood days. There was, I believe, the biggest aggregation of 18-carat characters in Port Costa during its first fifty years than ever existed in any other small town in the state, and it will be my pleasure to mention a few of them. So, I will begin with a quotation from an old poem:

Backwards, o backward, turn Time in thy flight.

Make me a child again, just for tonight.

And, So, I will ask all of you to become children with me, just for tonight.

Jeremiah Patrick Casey was born in the small town of Macroom, Co. Cork, Ireland and, by the way, today, Nov 8th, is his birthdate. He was one of a large family of fairly well-to-do farmer folk. The farm however, was not large enough to provide much of a future for so many and it was necessary for some of them to emigrate. My father was the first of them to emigrate, he came to San Francisco to a cousin, Cornelius Lyon, who had been in California for some years and had made a small fortune from a chain of blackboot stands. Mr Lyons was then known as the Champion Bootblack of the World, he always wore a wide leather belt studded with stars, with this inscription on it. He was recently mentioned in Herb Caen’s column. He had started with a small stand near the old palace hotel and had blackened the boots of many of the early day millionaires, among them The Big Four of Virginia City, Fair, Flood, Mackay and O’Brien. These men also gave him stock tips, from which he made much of his money, and by the same token lost it all too. At the time of my fathers arrival in San Francisco, Cornelius Lyons had a beautiful home in Rincon hill, which before the 1906 fire was the swankiest residential district in San Francisco. He had a coachman and two maids, the height of elegance and luxury, he wanted to make a bootblack of my father, but in those days most immigrants from Ireland followed the type of work they had done at home and so my father, after a short stay in San Francisco, went to Dixon to work on a farm. I often heard him say he worked from dawn till dusk for a dollar a day and his board and that the men had to pay 25c a bucket for drinking water, it was so scarce. After a couple of years, he went to Vallejo where another young Irishman Dennis Crowley, whom he had known at home, was working at the old Sperry Flourmills. The two energetic and enterprising young men came across to Port Costa and opened the Port Costa Hotel on the waterfront. When Dennis Crowley married a Vallejo schoolteacher, my father then took over the Ferry Exchange Hotel, a few doors away, and not long after, he married Mary Boyle. When Jeremiah Casey married he was close to forty years of age. In those days men had close to the price of the license before taking on the care of a wife and family. Four children were born of this union: Patrick, who died in infancy: John, who died in 1949: Jerry, who as you all know, died very suddenly January of this year (and how he would have loved to be with us here tonight) and myself, who ended up on Welfare in San Francisco.

Judge Casey had four grandchildren; John Desmond Casey, a young man of 25 who teaches at the Claremont Jr. High School in Oakland and who is here with us tonight. It is upon him that the perpetuation of the Casey name depends. Jerry Casey had three daughters, Miss Morris Barnett of Concord, Miss Katherine Gass of Martinez, and Maura Casey, who teaches at Oakland High School and lives with her mother in Martinez.

Shortly after taking over the Ferry Exchange Hotel, my father started the study of law. There were, of course, no such schools in the vicinity but he was an avid reader and acquainted himself with sufficient law to conduct his office when he was elected Judge. He was known ever after as Judge Casey, his name and fame spread far and wide and everywhere his children went, be it to distant schools, or to war, or to positions away from home, they always met someone who knew or had heard of their father. I will give you one illustration. During world war one, the San Francisco Examiner asked for donations of one dollar for a cigarette fund for the soldiers. The name of the donor was to be sent to the soldier, along with the cigarettes and, he, was to write his thanks. I received a letter from a sergeant Joseph Mulligan from an Eastern state thanking me and asking me if I was related to the Casey who had the hotel near the big ferryboat. Now, wasn’t that a coincidence: Three or four million men received cigarettes and I picked one who had known my father. Perhaps Joseph Mulligan passed through Port Costa and had to wait for a train, or perhaps Judge Casey had given him a few days in the Jug. The Sergeant never said.

No mention of my father is complete without a few stories told about him in his judicial capacity. One day he was ridging to Martinez in his horse and buggy when he stopped to pickup a weary hobo, who happened to be an Irishman. My father said: Do you know who I am? No, said the man, I’m Judge Casey from Port Costa, now my good man, you’d be a long time in Ireland before you’d be riding with a judge. You’re right, said the hobo, and you’d be a long time in Ireland before you’d be a Judge. Another time a few vagrants were up before him and as each stood in front of the Judge, he was given ten days in jail. The last man, thinking he would get off lightly, said his name was Casey. Is that so?, said my father, well you can take 30 days in jail for disgracing the name of Casey. Another time, when the Judge fined a vagrant $10, the man said flippantly: Oh that’s easy; I’ve got that in my jeans. Oh you have, said the Judge: Ten days in jail, do you have that in your jeans?

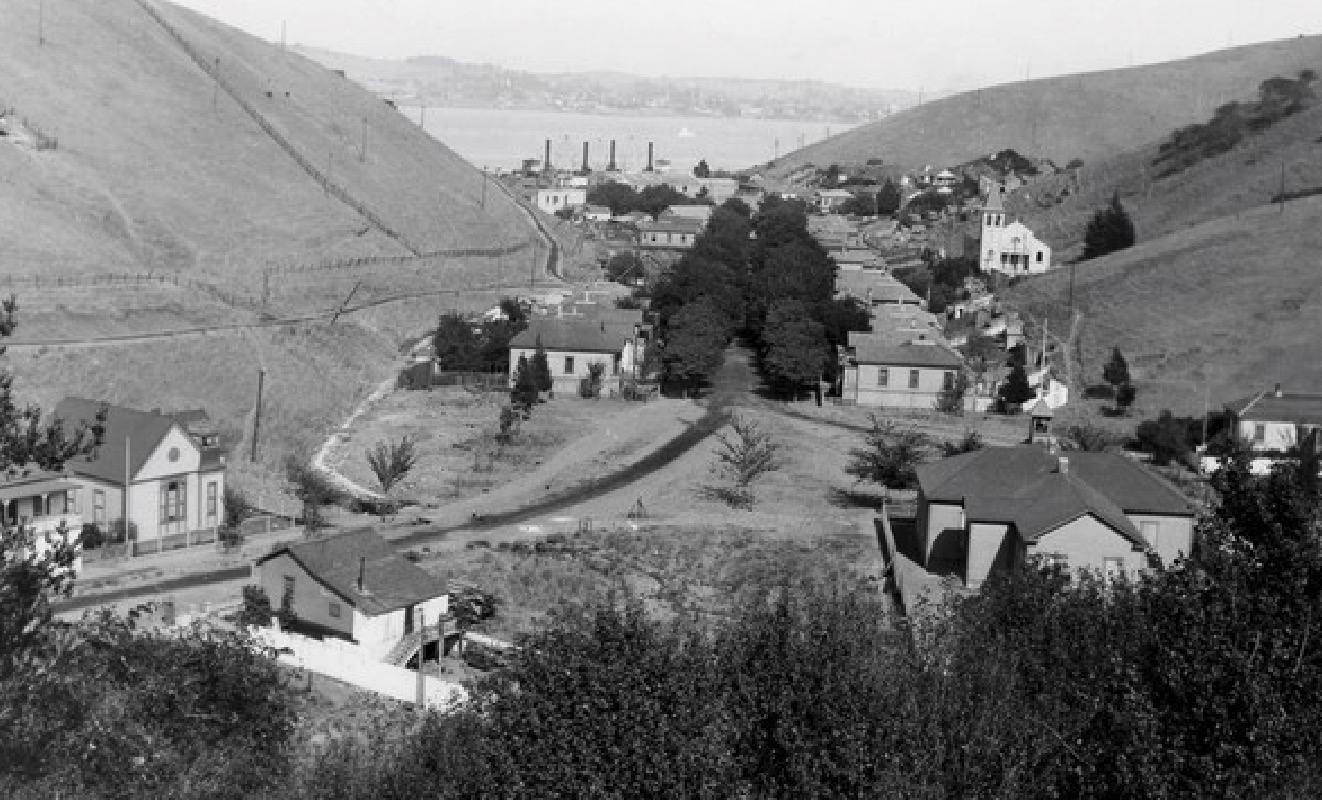

In Politics my father was a staunch Democrat, the poor mans party as it was known, a republican candidate didn’t stand a chance. Days in the Ferry Exchange Hotel were hectic during my childhood. The grain warehouses were at their busiest and it was common to see several ships tied up to the wharfs and more waiting in midstream to unload ballast and then load with wheat and barley for European ports. Much of the barley grown in California went into the making of the famous Dublin stout. The waterfront hotels were filled with young giants from Ireland, men of powerful physique who tossed around hundred pound sacks of grain as if they were filled with cotton. They worked hard and drank hard, for there was little else for them to do; no amusements, no library, no night schools, nothing but long hard hours of labor and a wee drop when the days toll was over. Their club was the saloon where they gathered at night, sat around and talked and played cards, there were no “taverns” in those days; they were saloons or bars and they were decent places in comparison with the dimly lit dens of today. Women were not allowed but the kids ran in and out all day and were safer there than they are on the streets today. As the poet said: I cherish such fond recollections, of the bar and the low-ceilinged room; of the mirror and rail and the sawdust-filled pail; Saloon, Saloon, Saloon. These men had little book learning but they did have a native wit and sharpness that stood them in great steed if they thought they were being imposed on. A few months ago there was an article in the Oakland Tribune by a Timothy O’Keefe, a St. Mary’s student. It, no doubt entailed a great deal of research but I certainly resented the slur on my old hometown when he said that murder was not uncommon. I never knew of or heard of a murder being committed. There were fights aplenty, as the Irishmen in those days were quick with their tongues and fists when the occasion demanded, which was often. These men led, on the whole, rather lonesome lives. Most of them had neither kith nor kin in the country and many never married.

When fires and the teredos destroyed the warehouses, and the grain was shipped directly to San Francisco by freight cars, their kind disappeared, they were a great breed, hardworking and hard drinking, but honest and decent. They held womanhood in reverence and there was no safer place for a woman at any time of day or night than on the streets of Port Costa. May the good lord have mercy on them, for we will never see their likes again. During the winter months when work was non-existent in the warehouses, my father and Dennis Crowley supplied the men with board and room without cost. Such was the generosity of men like Crowley and Casey that they could not bear to see any one hungry or homeless. They were often paid with ingratitude for their kindness, but no one was ever turned away. They took their religion seriously and the greatest of its tenets was charity. Many a poor priest in those days found food and shelter with them until he was established in a parish. And their charity extended to others as well. I heard my father say once that he was the first contributor to the building fund of the Congregational Church in Port Costa.

The old waterfront was a lively place in those days. First came Nealie O’Neill’s general store. Nealie married Josephine Dreschler, one of our schoolteachers, and the family moved to Vallejo when he retired. Next on the waterfront was Dennis Crowley’s Hotel. His children, with the exception of one, became schoolteachers and are now living in Berkeley; then came Jerry Donahue’s saloon; next the old scab house, so-called because during the early day warehouse strike, men were sent from San Francisco to break the strike, and were domiciled in the hotel which was promptly dubbed Scab House, and which name remained until the end. After the strike, no man ever again went to live at the hotel, and it was in this big, vacant dining room that we all learned to dance to the tune of a harmonica or old accordion. Next, came the little store of Sam Jacobs, a kindly little Jew and true friend of my father. Sam spoke French fluently and often interpreted for the French sailors when they were brought before my father on charges of disorderly conduct. And who could blame them for getting a bit out of hand after being cooped up on a sailing ship for months at a time. Sam would intercede for them and my father would give them some good advice and send them back to the ship. Next came Louis Raffetto’s saloon; then John Lacey’s saloon; then Cashman’s, then the Ferry Exchange Hotel, and a little barbers shop whose motto was “satisfaction guaranteed or your whiskers back”; Wells Fargo, the Post office, and last, Frank Emmon’s saloon. On hot summer days, there was always a delightfully cool breeze on the back wharf and it was a big treat to watch the river boats, the Modoc and the Apache, from San Francisco dock around five in the afternoon and unload supplies for the hotels.

Then uptown lived Mrs. Kate Hurley, the postmistress for 50 years; the Burlington Hotel conducted by John Buckley and afterwards by the Adolph Boehm family; Butcher O’Connell’s shop where each child who paid the family bill would get a slice of baloney half a foot long; Jerry Burke’s Hotel and saloon, where Devil Mahoney went courting the waitresses and where one night he fell into a big barrel of water when chased by Jerry; the little Chinese laundry man, Ah Too, whose life was made miserable on Halloween by the town lads, and at the end of the Valley the dear little three-room wooden school house, presided over by our three loved and dedicated teachers, Mrs. Mary Bulger, the principal, who turned out some of the brightest students in the county; Josephine Dreschler, afterwards Mrs. O’Neill, and Miss Julia Barry, who lived miles away in Franklin canyon and who came to school, rain or shine, first on horseback in her younger days and later in a horse and buggy. There were no juvenile delinquents in those days. The teachers and the dear, kind parents were strict disciplinarians and if you got a belt at school you would get another at home, so great was the confidence of the parents in the teachers. We had simple amusements, which cost little or nothing. Dancing was the chief diversion when we were growing up and many the Saturday we went to Crockett, danced all night and walked home up the railway tracks. Sometimes if we were lucky, we got a ride home on the switch engine but, woe to the boys on the engine if it was found out. At least once a year the Hibernians gave their grand ball. The children were trained for the program, which proceeded it, by Mrs. Bulger, our principal and I’m sure many a fine actor was lost to prosperity for lack of opportunity. Gracie Allen, of movie fame, was a frequent visitor to Port Costa in those days. Her sisters, Bessie and Hazel Allen, came up from San Francisco on Friday nights to give dancing lessons to the Port Costa children on Saturdays and they stayed at my father’s hotel. Occasionally they gave a program in the Forester’s hall and Gracie would take part. Every child in Port Costa would learn to swim the hard way. There was no old swimming hole, with the exception, perhaps, of a stealthy nocturnal dip in the reservoir from whence came our water supply and God help you if you were caught. We all learned to swim by jumping into 20 feet of water or by falling in or being pushed in and struggling to shore as best we could. When I look back now I realize how very dangerous it was to rear children on the waterfront; the railroad tracks with trains rushing back and forth all day long on one side and the water on the other. They say there is a special providence watching over drunks and children and I believe it is so, for I do not recall any child dying from having drowned, though some of them had mighty close calls. Whenever one fell into the bay there was always someone around to haul him out. And, now, I believe I have literally and figuratively covered the waterfront.

In the early 1900s my father and another Irishman, John Twomey, opened a steam beer brewery in Port Costa, at that time the only brewery in the county. The beer was sold in Martinez, Crockett, Rodeo, Pinole and Port Costa. It was taken to those towns in a big, high iron wagon drawn by powerful draught horses. Casey’s steam beer was food and drink for a man, and, if you drank too much of it, and ran into Jim Ahern, the constable, it could be a night’s lodging, too. Many a big schooner of it I hoisted on a hot day. And the price was 5c for a big glass. During World War I the government decreed that any establishment making or selling liquor, which was within seven miles of a naval or military station, had to close. This was just before Prohibition went into effect. As Port Costa was less than seven miles from the Mare Island Navy Yard and the Benicia Arsenal, my father had to close down the brewery, and lost every cent. The government did not give him one penny for his years of hard work and the money invested. He made no attempt to convert to near-beer. He was no longer young and it would have been a costly move, as well. And I’m sure he often thought when he tasted the so-called near-beer that the man who named it was a poor judge of distance. Such was the sad fate of Casey’s famous steam beer, the likes of which has never been made since.

After my mother’s tragic death in 1907, a blow from which my father never fully recovered, we left the hotel and moved up into the valley. My father was fortunate in having a dear, kind sister (Aunt Ellen) who gave up her position in San Francisco and came to live with us in Port Costa, to care for his three little children and to nurse him through the many terrible sieges of asthma from which he suffered through the years. Aunt Ellen remained with us until my father died.

In 1908, at the age when most men are thinking of retiring, my father entered into an entirely new life. He was elected to the board of supervisors of Contra Costa County and held that office until his death in 1924. His funeral was one of the largest ever held in the county and many beautiful tributes to his memory were published in the county papers. He was laid to rest in the family plot in St. Vincent’s cemetery in Vallejo.

Like all small towns many of the men of Port Costa had nicknames. There was Chicken Murphy and Horse Murphy and Fiddler Murphy; Bull Cronin, Chief Crowley, Strong Con Kelleher and Devil Mahoney, among others. Strong Con Kelleher, a man of good family and education threw it all away, alas, by trying to drink up all the liquor in town. His powerful voice could be heard all over town on a calm summer evening, extoling the merits of Tom Heenan, in the well-known ballad of the day, “The Bold Benicia Boy” written by some local poet. Tom Heenan, the Benicia Boy, fought Sayers in England with bare fists. And it was on a barge in midstream on Carquinez Straits that gentlemen Jim Corbett of Hayes Valley in San Francisco and Choynski of the Mission battled it out with bare fists in one of the longest fights on record. At the last moment, the authorities decided the fight would be illegal and so a barge was hired and it was conducted thereon.

There was Patsy Mahoney, commonly known as Devil Mahoney, a giant of a man, who reared a large family of fine children. Patsy loved to tell stories on himself, especially the one about the monkey. It seems he was working on a French ship. The captain had a pet monkey. One day the Captain went to San Francisco and Patsy grabbed the monkey, hid him in a grain sack, and took him down into the hold of the ship. The Captain returned from San Francisco sooner than expected, and missed the monkey. When the five o’clock whistle blew, and the men began coming up out of the ship’s hold, the Captain stationed himself nearby to watch for his pet. Up came Patsy with the sack. He must have gotten an awful jolt when he saw the Captain but it would take more than that to non-plus Patsy. With an air of annoyance, he threw the sack at the Captain’s feet and said: Here, take your damn monkey out of my sack.

Then there were the Nelson brothers, two big Swedes, the gentle Billy, who converted to the Salvation Army and Nick, the rough, tough ship foreman. One day Nick shouted down into the hold of the ship: Billy, how many of you are down there? And Billy answered very solemnly: Only me and Yesus. And said Nick: You come on up and let Yesus stay down there. I remember, too, big Dennis Shelley, father of Congressman Jack Shelley, and Tommie Maloney, afterwards the popular and beloved Senator Thomas Maloney, whose wife, Helen Twomey, was the daughter of John Twomey, my father’s partner in the brewery venture.

Then there was an Irishman named Issac Jermyn, believe it not, whose forebears very probably were the English Earls of Jermyn, and whose daughter, Mrs. Theresa Jermyn Paulian is private Secretary to the President of the Pacific Gas and Electric Co. And Louis Buttner, a telegrapher in Port Costa, who afterwards became County Treasurer of Contra Costa County and whose two sons went on fame and fortune. Edgar, an electrical contractor in Oakland, and Harold, a vice-President of the A.T.&T Co.

Then there was George Ward, Superintendent of the Southern Pacific Company in Port Costa for many years and whose daughter, Mrs. Ella Ward Ryan, a retired San Francisco high school teacher, who is here with us this evening. George Ward took a great interest in the Port Costa School. He was a trustee for many years and along with Dennis Crowley gave much of his time to the interests of education. And there was Port Costa’s first doctor, Dr. Jahel Stackhouse Riley. I have often wondered how those two names got together with Riley. And Dr. McFarlane of Benicia. If you needed him, it was necessary to phone over and by the time the good doctor walked down the length of Benicia to the ferry boat and waited perhaps an hour before it pulled it out, the poor patient could be dead and buried. And Dr. Rickey, who had the first automobile in town and how all the kids and chickens scurried for safety when he chugged down the valley in his merry Oldsmobile. Ah, the good old days. They were indeed days of wooden ships and iron men; the days when men were men and women were gland of it.

And always in the background was my father, the kind, benign patriarch; a man of generous impulses and the hospitable ways of the pioneer. Any one in need never failed to find food and shelter at his hands. He was so noted for his high-mindedness and fairness that his name was a password for justice, integrity and honesty. It was said of him that his word was as good as his bond. His heart and purse were ever open to the unfortunate and though calls on his generosity were many, he always responded with willingness and liberality. He was an ardent and brilliant Gaelic scholar. The name, Casey, in Gaelic means warrior and he was, indeed, a warrior, always battling for the right, a man who had the courage of his convictions and whom no one could sway, once his word was given. A staunch and faithful citizen of his adopted country, he never forgot his native land and its cause always had his moral and financial support. I know he must be smiling to himself as he listens to what he would term “extravagant praise” and I’m sure it would remind him of the following little story:

An Irishman died leaving a widow and small boy. He hadn’t been the best husband in the world; had taken one too many on occasions and spent his money recklessly, and so on. At the funeral mass the priest was giving a eulogy over Pat’s remains. He told what a kind and loving husband and father he had been; what a good citizen and church member he was. The widow listened in amazement and finally said to the little boy: Johnny, go on up there in front and see if that’s your father in the coffin.

God gives us men; men who the lust of office does not kill; men whom the spoils of office cannot buy; men who have honor; men who will not lie; men, sun-crowned who live above the fog in public duty and in private thinking.

And, now in conclusion this little tribute:

My Father;

Unknown in the halls of fame

Yet truly great, my Father:

Great in the greatest things of life.

Not great in earthly wealth

But greatly generous

Generous in kindly counsel,

Patience and in love

Unsung in songs but shrined in loving hearts,

My Father:

Thank you.